Since I mentioned the monument in the middle of Haverfordwest in my last post, I thought I might as well slip in the short story I wrote about it.

So here it is...

DANCES ON THE HEAD OF A PIN

‘Well, man. And you are?’

‘I am? I don’t understand you, sir.’

‘I am asking your name, man. What is your name?’

‘Oh, I am William. That is my name, sir. Yes. William.’

‘Very well, William. Let us begin this examination.’

……….

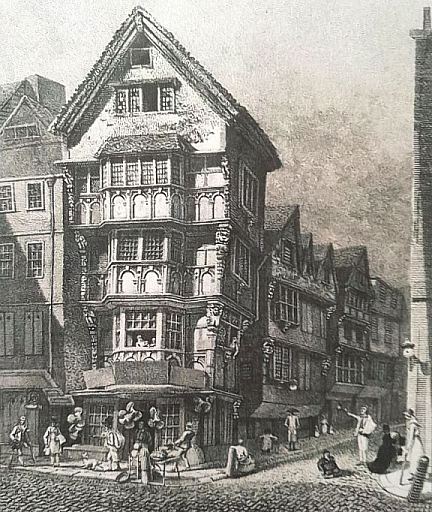

There’s a lump of stone. A heavy piece of uninspiring Edwardian workmanship. You’ll find it in the cleft of the road, a little way below the church. It’s an unpleasant red, like steak that has begun to go off. It is polished like prized linoleum and shaped much like the pillar box that stands close by, along with a green plastic litter bin, a grey cubist telephone booth and a lamppost bearing traffic prohibitions. It’s surrounded by a low stone wall and a flight of slate-slab steps that connect one fork of the road to the other. Wall and steps provide a useful perch for the inevitable colonisers of street corners.

Like the adolescent couple who sit there now, smoking. He finishes a can of lager and crushes it into a ball.

‘I’m doing a survey. Can I ask you some questions?’

The boy shuffles away, along the step, but the girl is more curious. ‘Yeah, okay. Right. Go on then.’

‘Do you visit the town centre often?’

‘Yeah, well, sometimes.’

‘You live in the area?’

‘Yeah.’

‘What concerns you?’

‘What you mean?’

‘What questions keep you awake at night? What tugs at your heart and soul? What worries you?’

‘Oh. Right.’ She nudges her boyfriend. She thinks she knows the answer I want. ‘You mean jobs and stuff, right?’

‘Aren’t no jobs,’ mutters the boy.

‘Jobs,’ I jot down.

‘And housing. Yeah, ‘cos we can’t find nothing.’

‘Housing.’

‘And…’ She’s being tentative, trying to gauge my reactions. ‘Is it drugs? Is that right?’

‘What about transubstantiation?’

‘You what?’

‘Transubstantiation.’

‘Is that like, trannies? Gays, like?’

‘Not really.’

‘Don’t know nothing about it, then,’ says the boy. He’s had enough. He scrambles to his feet, dragging the girl with him, and tosses the crushed can over his shoulder. It lands at the base of the polished red stone, not far from the litter bin.

A businessman trots hurriedly down the steps, cutting off the corner as he hurries to his office.

‘Can I ask you your views on transubstantiation?’

‘No time, no time.’ He shoos me away.

An old lady, puffing up the hill, takes the opportunity to pause for breath.

‘Have you any thoughts about transubstantiation?’

‘No use asking me, love. Haven’t got any thoughts except about getting home and putting the kettle on. Electricity substations, was it? I don’t know anything about that, except my bills are too high.’

She wheezes on her way. A lorry passes and a cloud of acrid fumes envelops the polished red stone.

……….

‘William, you must answer us,’ says Justice Horne. ‘Do you understand?’

‘Oh yes. You ask things and I answer.’

‘That is right. So listen to Father Gregory’s questions and answer him honestly.’

‘Yes. I am an honest man.’

Father Gregory leans forward, eyes big and dark, almost pleading. ‘But are you an honest Christian, William? Do you believe in your soul’s salvation through the sacrifice of our Lord, Jesus Christ and the intercession of the Catholic church?’

William gapes. ‘I go to church,’ he says, slowly.

‘Very good. And when you attend Mass, and the priest raises up the host, before the high altar of God, do you know what he is doing?’

‘He’s holding it up.’

‘Yes, yes, but this is important, William. The holy Eucharist. That is what we are speaking of. The bread and wine of the Mass. Do you believe that the blessed sacrament is truly the body and blood of Christ, Our Lord?’

‘Oh no,’ says William, cheerfully. ‘It is only bread and wine. I was told that.’

A hiss.

‘Do you understand what you say, man?’

‘I know it is bread and wine.’

‘But in the course of the Mass, it becomes the actual flesh and blood of Christ, is that not so?’

‘No, no, I don’t eat man flesh. That would be wicked. It is only bread and wine. I was told.’

‘You were told wrong. Who told you this wicked lie?’

‘I was told. I must believe it is only bread and wine, or my soul will burn in Hell.’

‘You are wrong, William. Your soul will burn in Hell if you do not acknowledge, here, before us all, that the blessed sacrament is the very body and blood of Christ. Say it!’

William’s slack lower lip hardens and juts out. His dazed eyes narrow as he tenses with a flood of obstinacy. It is, doubtless, the unthinking obstinacy that comes to his rescue when he is jostled in the street, or when bullies order him around. ‘Will not! It is only bread and wine. I was told.’

Father Gregory sits back, shaking his head, his face racked with misery.

Justice Horne knits his brows as he surveys William. ‘A sad business. Take him back to his cell. We can do nothing with him.’

Father Gregory clasps his hands in fervent, silent prayer. Justice Horne waits for him to finish, then crosses himself.

‘A bad business.’

‘A terrible business, Justice. A terrible heresy that will claim countless souls if it is not rooted out.’

‘He is a simpleton, of course.’

‘Clearly, but a misguided one, and those who taught him to spout these vile lies will surely feel God’s wrath. But it is his soul that is our business now.’

‘He is a mere child in a man’s body, is he not? Talium est enim regnum caelorum. Such is the Kingdom of Heaven.’

‘Yes. Yes, he is a child. Sinite parvulos et nolite eos prohibere ad me venire. Suffer the little children and forbid them not to come unto me. It is for us to lead him back to the true God, and let the simple soul enter the gates of Paradise.’

‘Quite so,’ says Justice Horne. ‘A child, most dear to God. Better to have found a home and refuge in a monastery than be cast adrift in this busy and relentless world.’

‘Indeed. In the bosom of Mother Church, he could have found true sanctuary.’

‘But alas, there are no monasteries now, for such simple souls and it is left to us to give him peace – us to decide what must be done with him.’

‘Yes. A solemn duty.’

‘We’ll burn him, of course.’

‘Of course! He must burn. Better for him to face the agonising purification of the flames now and, in them, find repentance, than to face the fires of Hell for all eternity. I would be betraying my duty for the care of his soul, otherwise. For his own salvation, he must burn.’

Justice Horne nods politely. ‘And for the salvation of this land – for the sake of peace and order. As our noble Queen Mary and the law have decreed, so shall it be enforced. Heresies will be rooted out. We cannot permit beliefs contrary to the law—’

‘To the teachings of Holy Mother Church.’

‘To the teachings of the church, as decreed by the law. There must be one understanding of truth in this state, or how can the centre hold? If it were seen that a simple man could defy the law, with wayward views, there would be anarchy. There would be chaos. The rabble would rise and gentlemen would never be safe again. Peaceful order is everything and it is for us to enforce. If only to teach others the wisdom of obedience, he must burn.’

‘Amen.’

‘William. Look there. Do you see the stake they have prepared for you? The chains to bind you to it? Do you see the faggots that will be piled around you? Do you hear the baying crowd, come to see you burn?’

William stares, vacantly. Does he understand?

‘Repent, William. Stand up before this crowd and recant your heresies. Acknowledge the teachings of the true church, as established by the law. Tell them you admit the truth, that the bread and wine of the Eucharist is truly the body and blood of Christ. Tell them that, William, and you will not burn. Do you want to burn, William?’

‘No! I don’t want to burn. I don’t like being burnt.’

‘So tell them.’

‘But if I tell a lie, I will burn in Hell, forever. I don’t want that. No. This will be quicker, will it not?’

‘So be it, William. If you will not repent… Take him. Let us do this thing, before the crowd grows restless.’

‘These clouds look black, Father Gregory. Is that a drop of rain? I hope so. Better that sodden faggots will smoke and smother him. I confess, I take no pleasure in the sound of these screams.’

‘No, Justice. Don’t pray for rain. Pray rather that the fire burns and his screams continue in unabated agony to the end, for in them pour forth his pleas for mercy to Our Lord and his blessed mother, who will lead his soul to salvation. Only thus is a soul saved and the truth maintained.’

‘Even thus,’ agrees Justice Horne, settling back in his chair, to watch to the finish.

……….

Two middle-aged women, well-dressed, heels clicking, are winding up the hill, pausing at the lump of stone.

‘Excuse me, would you be willing to answer a question or two? It will take no time at all.’

One looks wary, lips pinched, prepared to brush me aside, but the other is too polite. I don’t look like a mugger, or foreign, so perhaps I am all right.

‘Well, maybe. What is it about?’

‘Could you tell me your views on transubstantiation?’

‘On, er…’ They look at each other. The reluctant one is unwilling to voice her ignorance. The polite one gives an embarrassed laugh. ‘I’m sorry. I don’t know what that is.’

‘It’s something to do with the EU,’ snaps the other. ‘More typical bureaucracy.’

‘Not quite,’ I say. ‘Do you go to church?’

The reluctant one nods. The other repeats her embarrassed laugh. ‘Not at often as I should.’

‘Transubstantiation is the belief that, in the celebration of the Eucharist, the bread and wine becomes the actual body and blood of Christ.’

‘Oh. Well. I’ve never really thought about it. Um. Why?’

‘You will have noticed this monument here.’ I point to the lump of stone. ‘It commemorates the burning at the stake of a man who refused to accept the principle of transubstantiation.’

Their gaze follows my pointing finger and they read. “On this spot, William Nichol, of this town, was burnt at the stake for the truth. April 9th 1558.”

‘Well I never. Horrible. I mean, horrible to think they did things like that.’

‘The priest who helped to condemn him died a martyr, certain of his place in heaven. He was hanged, drawn and quartered, for refusing to deny transubstantiation.’

‘Oh nasty. I don’t know which is worse.’

‘This burning is listed in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. “The suffering and martyrdom of William Nichol, put to death by the wicked hands of the papists.”’

‘Well, fancy!’ says the polite one.

‘Oh, papists,’ says the other. ‘I don’t care much about them. It’s the Muslims I worry about. And the Poles.’

‘Of course,’ I say, and let them depart.

I look again at the lump of stone. A small dog, running loose, is sniffing around it. He cocks a leg, pees and scampers on.

William Nichol’s ashes were dispersed long ago, mingling with the stardust of creation. So too were the remains of Father Gregory. Different agonies, but the same stardust. Whereas I – I merely fell asleep in my bed, having gone on, for many years, to administer justice in the name of Good Queen Bess, the Anglican communion and the laws of the land.

I don’t seem to have mingled with anything. I linger. It’s the world around me that shimmers and transforms. Did the centre hold? It shifts. I no longer know where it lies. What is it we believe, these days? I am out of touch. Some days, I no longer remember why I had to burn William Nichol, but I know it must have been important. So I come here, clip board in hand to remind myself. Of course he had to burn. Didn’t he?

No matter. Times have moved on. There will always be another cause worth dying for. Worth killing for.

Who shall we burn today?