Here's another post about old houses.

Some places have a lot of easily splitable or workable stone, and if you had it, you used it, but elsewhere the most convenient material for building houses was wood. After the last ice-age, Britain was largely covered by woodland, although that was seriously reduced with the arrival of agriculture. As an aside, I say woodland rather than forest because in Norman times ‘forest’ was a term that referred to royal hunting grounds with gory penalties for poaching, rather than an impenetrable blanket of trees.

The woodland was largely oak and hazel which, when combined, made very effective structural materials that have come to epitomise Tudor England. Oak – especially heart of oak – is hard, strong, resistant to rot and woodworm and was used (is still used, if you can afford it) as the framework for buildings, with huge timbers pegged together, allowing a bit of charmingly quirky shifting and creaking.

The spaces between the timbers were filled with woven split hazel wattle, liberally daubed with a mixture of clay, mud, straw and cowdung. Yummie.

One of the earliest types of timber construction used cruck beams, which made use of the natural curve of some massive timbers, taking the weight of the house from roof peak to ground. Use two or more pairs of crucks, as the basic support for a house, and build the rest around them.

Smaller curved timbers were also used to brace framework, and stop the whole thing from collapsing. Bayleaf, a satisfyingly elegant wealden house at the Weald and Downland museum illustrates the bracing beams, in a house that is more wattle and daub than heavy timber.

But timbers were often used more liberally. Two variations were common. Box framing produced a grid of vertical and horizontal timbers. This was especially common in the west of the country.

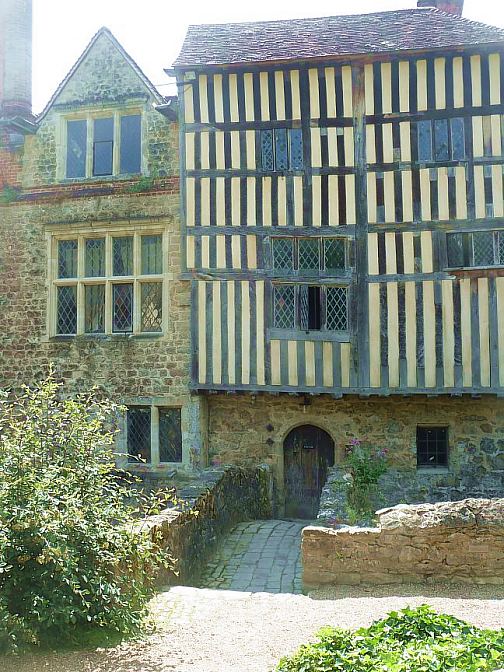

In the east, close vertical studwork was favoured, as in this example at Ightham Mote in Kent.

The traditional image of Tudor England is of two-tone houses with startlingly black timbers and brilliant white plaster. In reality, untreated oak will weather over time to a silvery grey.

Limewash or plaster was often used to protect not only the wattle and daub but the timbers too. This house in Eardisley (Herefordshire), illustrates both plastered and exposed timbers.

Plastering, especially in the east, was taken to decorative extremes with the art of pargetting, as with this example in Saffron Walden.

Ship’s timbers, blackened with tar, produced the picture-book image of black and white houses, especially in the west and Welsh marches. The contrast of timber and plaster was recognised as a forceful visual statement, leading to timbers being used not merely as supporting framework but as decoration in their own right. The Feathers Inn in Ludlow is a prime example.

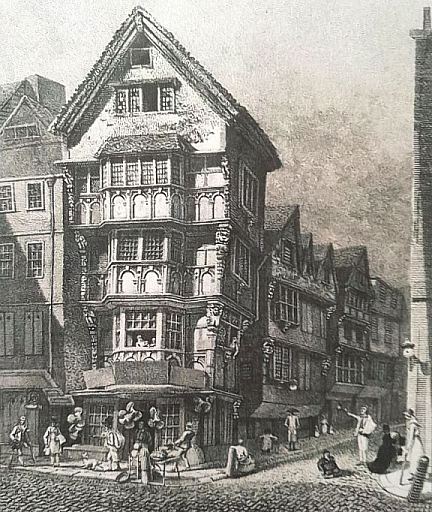

The Feathers also illustrates how timber framing could allow houses to increase in height, expanding as they did so, with jutting floors. In many Medieval and Tudor towns, houses on either side of lanes could jut out so far they nearly met. Most examples were demolished and replaced in later times. One five-storey example that survived until the 18th century, to be recorded in an etching, stood on the corner of Chancery Lane in London, resembling the stern of a galleon.

By Tudor times, brick was becoming ever more common as a building material. Timber was still used as framework, but herringbone brickwork began to replace wattle and daub as the infill.

The appeal of at least the appearance of half-timbering survived its decline as a genuine means of construction. The Gothic revival that began in the 18th century resulted in stone or brick houses being given a fake half-timbered facelift, like Plas Newydd, in Wales, a stone house “improved” by the Ladies of Llangollen.

The lure of Merrie England reached the spread of middle-class suburbia in the 1930s, with a rash of mock-tudoring. Never miss an opportunity to slap on a bit of timber.

Less a comment and more a way of seeing if it makes it onto the blog!

ReplyDeleteDidn't know about the old definition of forest, nor had I come across pargetting. I shall be looking out for these features plus the others. The building on the corner of Chancery Lane looks like something out of a Terry Pratchett novel!

ReplyDeleteEast Anglia is the best place for pargetting, apart from the cat on the side of my house.

DeleteWhen you say the cat on the side of your house... (Are we talking pargetting or feral feline?)

ReplyDeleteA pargetted cat on the side of the house, but admittedly done with concrete, not plaster.

Delete