The Tudors didn’t invent brick, or chimneys, but they experienced a small revolution in house-building, by making common use of both.

Bricks, made of clay fired in a kiln, had been around since Roman times, but they had to be mass-manufactured so they had less appeal as a cheap and readily available material for building than timber, wattle and daub. The wealthier could afford them, and so, as the country grew wealthier so did more and more people. Ironically, the Black Death helped. It may have wiped out between a third and a half of the population, and put back its recovery by several centuries, but England began to move from being a third-world supplier of raw materials to a manufacturing economy (okay, the Welsh kept goats and Scotland was Scotland). There was less pressure on land and… well, let's just settle that the country got richer, with funds available to be spent on building more substantial and durable houses.

Despite the Wars of the Roses, Spanish Armadas, Civil Wars and general uprisings, the country also became a little more civilised. There were less anarchic warlords chasing each other around and laying siege to their castles, which were no longer quite so safe now that gunpowder was on the scene. So castles of stone with walls twelve feet thick gave way to country manors and palaces built of brick.

Chimneys had long existed in buildings that were several storeys high, or there would be no chance of heating them without choking everyone to death. Stone-built castles were one obvious example. In modest urban dwellings of only two floors, a smoke void at the rear would be sufficient, but for prosperous merchants who had no option but to build upwards rather than outwards, because of lack of ground space, chimneys were de rigeur.

Where there was space to expand, in the country, it was more normal, in Medieval times, for at least one hall to be left open to the rafters, to allow the smoke to rise and escape through high vents.

Brick changed this. One of its benefits was that, unlike timber, wattle and thatch, it didn’t catch fire, so chimneys became a must-have feature of every house but the humblest hovel. Even in half-timbered houses, brick allowed a chimney to be added.

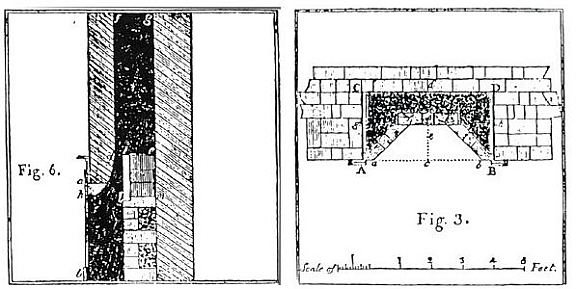

New houses could be built around a huge central chimney with several flues, bread ovens, and enclosed hearths. The taller the flue the better the draw on the smoke. The need to have a hall open to the rafters, was gone, and that meant that upper floors could be inserted. Blackened timbers, nursing old soot, hidden away in closed lofts are a sure sign that a house once was once open to the rafters.

Brick could be moulded or cut, and chimneys were regarded as a sign of status, so naturally chimney pots became a means of boasting and an outlet for artistic exuberance. No small discreet pot for the Tudors, with a cowl to keep the rain and jackdaws out. Tall and extravagant was the order of the day. If you had it, flaunt it.

Even when building with stone, the chimney was a dominant feature that demanded attention.

While chimneys allowed for upper floors and carried the smoke away quite successfully, the hearth usually remained much as it had been when it had occupied the centre of the hall. A serious bonfire was needed to heat a good-sized room. In some cases, fireplace were large enough to be almost rooms in their own rights - inglenooks, where people could sit cosily round the fire.

Raising the fire on firedogs or grates allowed a better airflow into the flames, but it wasn’t until the end of the 18th century that improvements were made, with the Rumford fireplace, shallower and angled to reflect more heat into the room and siphon the smoke away more efficiently. Since I always try to mention Jane Austen, General Tilney boasts that he has improved the fireplace in Northanger Abbey. Catherine, who hankers after all things Gothic, is not impressed.

Fires were not only used for heating, but for cooking, of course. Bread oven and charcoal ranges for saucepans could be added, but generally kitchens had open fireplaces with assorted ironware – spits and cradles and hooks - for roasting and boiling.

With the coming of the industrial revolution, coal replaced wood as the fuel. It produced very efficient heat but also unpleasant and noxious smoke. Roasting on a spit before an open fire was no longer possible without tainting the meat, so enclosed ranges were introduced, with an iron oven and, frequently, a water boiler with tap.

This did mean that the roast beef of Olde England became the baked beef of Modern England, which is mostly what is eaten today. They were roasting large joints on a spit before a wood fire in the Hampton Court kitchens when I last visited, but they wouldn’t let me try any. Health and Safety, I ask you.

No comments:

Post a Comment

comments welcome